| |

|

ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENTALISM

E.D. Michael

September 17, 2009

|

Long experience representing before public bodies clients who either demand or resist compliance with rules deemed appropriate in interpreting California environmental legislation leads to the conclusion that the environmental movement in California lacks a philosophical approach probably best referred to as "economic environmentalism." There has developed a massive literature relating economics to environmentalism but it has to do with either global or national concerns. Such concepts are too high-flown to be of much use when considering local environmental concerns. No definition seems yet to have been proffered that speaks to local communities such as Malibu. Close to home, economic environmentalism comes down to considering the usefulness of a contemplated project to improve the environment in terms of its practical effects measured against funds available for some other project.

ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENTALISM IN THE TRENCHES

The need for such economic consideration is clear, because environmentalism in one sense is a business and, apparently, a quite profitable one at that. This appears largely to have come about because the responsibility to allocated funds, mostly provided annually by Congress or by state legislatures, is delegated to individuals or organizations that feel the need to do so primarily to justify their existence. Aside from specifically funded projects by Congress and state legislatures, which one hopes are well reasoned, there are annually established grab-bags of money available to public agencies such as county departments of health or parks and recreation, to universities, to quasi-governmental entities such as conservancies, and to non-profit corporations which, although in theory are privately funded, function largely by grants of public funds. In fact, anyone who can fashion a subject billed as green buttressed by some claimed or demonstrated expertise can apply for funds to study it. According to the Coastal Commission's Marine, Coastal & Watershed Resource Directory, there are well over a hundred such potential recipients of environmental funds operating in Los Angeles County alone.

Coupled with this is the arbitrary and predictable position among politicians that if it's green, it's keen. Rare indeed is the politician who, although lacking any assurance of a rational scientific basis, comes out against a proposal billed as environmentally important. All of which brings us to Malibu and the underlying issue of whether a green project is undertaken because of its environmental significance or because of its economic benefit to those who are to accomplish it. Economic environmentalism is with us and is here to stay. Proposed projects need careful, independent review to determine their value and necessity if massive waste is to be kept as low as possible.

CLASSIFICATION OF ENVIRONMENTAL VALUE

Any rational critique of an environmental project requires some means of project evaluation. Even a casual review of projects proposed or accomplished thus far in Malibu suggests the need for some sort of project classification in terms of its environmental value. For example, consider the following project classification scale:

Class 1 - Critically important, requiring, if necessary, special funding implementation as soon as possible;

Class 2 - Highly desirable and deserving of implementation in the normal course of the governmental legislative and funding processes;

Class 3 - Ostensibly desirable and, upon objective review which is favorable, to be considered for implementation with other projects similarly evaluated;

Class 4 - Ostensibly desirable, but requiring additional research demonstrating either both economic value and funding feasibility;

Class 5 - Questionably of environmental value or feasibility and therefore to be rejected unless extensively revised;

Class 6 - Rejected as environmentally valueless or more harmful than any asserted environmental value.

FORMAL DEFINITION

"Economic environmentalism" may be defined as the view that without knowledgeable, objective, and independent review, a proposed project can be rendered largely ineffective, or fail, or actually harm the environment. Without such review, projects can be implemented by managers or politicians who lack the analytical ability to evaluate a proposed project, or who see such projects primarily in terms of their personal job security rather than environmental value.

By law, a project should not be funded unless subjected to such review. By "knowledgeable" is meant: with technical and scientific comprehension sufficient to fully understand the project's purpose and the proposed method of investigation. By "objective" is meant: without regard or comparison to the merit or purpose of any other environmental project either proposed or active. By "independent" is meant: review by an entity that has no financial or other remunerative interest in whether the project is funded and that is not answerable to the entity having the funding power. In practice, reviewers should act only in an advisory capacity. They should be hired by unanimous agreement of the controlling political body, and they should publish their evaluations and recommendations in time for public comment.

RELATION TO SUSTAINABILITY

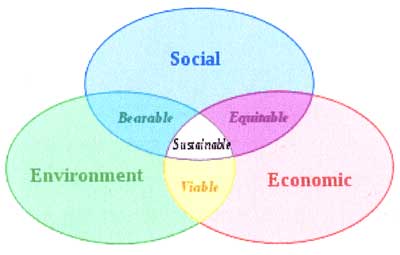

"Sustainability" is defined in various ways. Generally, it refers to development which meets today's needs without compromising those of the future. It recognizes any development as having social, economic, and environmental impact, and considers as sustainable those developments in which these impacts are in "ecological equilibrium" - fascinating idea indeed. Figure 1, a sort of Venn diagram from the Web Wikipedia, definition is useful to understand the concept.

Figure 1.

Although not specifically recognized in terms of these impact intersections, in projects coming before the Planning Commission or the City Council in Malibu such matters are routinely addressed to some extent. Malibu, probably like most jurisdictions today, is not able to fully analyze the sustainability of proposed environmental projects because of limited staffing. However, the aspect most commonly misunderstood in Malibu these days is project viability, i.e., the intersection between economic and environmental impacts. To reiterate, there are three reasons for this: [i] an imperfect knowledge of the environment on the part of the entity charged with fund allocations; [ii] the willingness of contractors to proceed in the face of such lack of knowledge and therefore with little chance of success, in the past known far and wide as boondoggling; [iii] the desire on the part of decision-makers to appear politically correct simply by spending. This, in turn, is the reason that the principles of economic environmentalism are especially important to consider in Malibu today.

* * *

|

|

|

|